A taste of traditional village life

After a rude awakening, Anna settles in to daily rituals and spirited encounters with the people of Ha Giang

It was 3.30am when the cockerel first crowed, an alarm all the more bone-jangling because it was right underneath the hut on stilts in which we were sleeping. Every 10 minutes or so that darn cockadoodle-do split the silence, until around the time when one actually might want to be woken up, at which point it went quiet.

Vietnamese village life is not without its challenges for the unsuspecting tourist. (Home-brewed rice wine the colour of pond water, anyone? More on that later.) But they are nothing alongside its many delights. We were in rural Ha Giang, a mountainous northern region of Vietnam, close to the border with China. Ha Giang is a six-hour drive from Hanoi, and a world away, a place where currently very few tourists visit.

Driving ever upwards into the mountains, we passed through a narrow gorge between two giant cliffs, the aptly named Heaven’s Gate. Beyond was a landscape of toothsome crags and wild forest and jungle, offset with the gentle, shimmering emerald of paddy fields. The mountains of Vietnam’s north, along with those of its interior, are where the majority of the country’s 53 minority groups live (the 13.8 per cent of the population who are not ethnic Viet), many of them upholding a way of life that has remained largely unchanged for centuries.

Our first night in the region was spent at a pretty French-owned guesthouse in the village of Panhou, its rice paddy surrounds reinvented as an exotically planted water garden. No middle-of-the-night cockerel crows here; just some fairly low-key frogs. In the morning we went to the nearby market in the district of Thong Nguen, where we saw women from two different tribes meeting to shop and, more importantly, to gossip

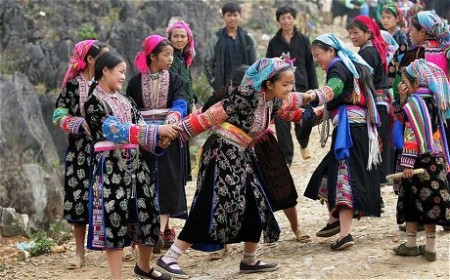

The Red Dao women wore a navy hemp outfit with a red trim. Their heads were haloed with a big coil of red trim, and on their chests was a large pewter necklace that looked more like the breastplate on a suit of armor. The Black Dao wore a black hemp outfit trimmed in white, and on their head was a black kerchief decorated with white cords.

Whichever their tribe, the men wore modern clothes. Our guide Quang told us that women, especially unmarried ones, had less sartorial freedom because their reputation as a “good girl” would be at risk if they chose to abandon the traditional dress. The youngest had abandoned one practice however – the chewing of betel leaves. The older women were all betel chewers, their blackened teeth considered by them and their peers to be beautiful.

Such is the comparative rarity of tourists in Ha Giang that we were as much an object of fascination to them as they were to us, a fact that lessened that uncomfortable feeling of voyeurism that you can sometimes suffer when you travel off the beaten track.

There was very little food to be bought – dried fish and pork was pretty much all that was left by the time we got there. Instead there were numerous stalls selling the yarns and the braiding that decorated the Dao costumes. When we walked out of the market up into the surrounding hillsides we quickly saw how self-sufficient the Dao were; why there was very little they needed to buy.

Every house was the Good Life personified: aside from the rice paddies themselves there were immaculate vegetable and herb gardens (the Vietnamese diet includes copious herbs and salad leaves at every meal, often added to a meat-based noodle broth called pho or bun). Most of the dwellings were traditional wooden affairs, the Red Dao houses built on the ground, the Black Dao houses on stilts. Outside several homes, a woman was winnowing rice using a large flat-bottomed basket, tossing the rice up high into the air to separate it from the dry husks.

Unfortunately, we had lunch at the home of someone who was going up in the world, which meant we ate our delicious picnic not in a picturesque traditional house but in a breeze-block carbuncle, breeze blocks being such a status symbol as to be like the Rolex watch of the Dao world.

We sat with the son of the family and a son-in-law, the former a city worker back to visit for the weekend, the latter still a country boy. They were both in their late twenties, yet the difference between the two was remarkable, the former confident and chatty, asking us lots of questions and telling us about himself with the help of Quang, and the latter not uttering a word, barely able to bring himself even to look at us. This was a typical distinction between city and country folk, Quang told us.

The next day we drove a couple of hours to the Phong Thien commune, home to the Black and White Tay and, as we were later to find out, that excruciating cockerel. The Tay villagers no longer wear their traditional costumes – they are nearer to the city, and its influences – yet it is still an ancient-seeming place. It was raining on our first morning and we saw one woman using a large leaf as an impromptu umbrella. In the paddy fields the women – and, yes, it is the women who work there – wore not only their traditional woven conical hats but a kind of backplate, also made of woven bamboo, to protect their body from the rain as they bent over.

Even aside from the rain, this was a watery place, with numerous little rills and jerry-built aqueducts made of rubber piping and bamboo, all designed to bring water down into the villages from many miles up in the mountains. We saw one local woman with the ubiquitous twin baskets, one on each end of a carrying pole, transporting her ducklings between home and paddy field, where she took them daily to gobble up insects and snails.

Our walk around the local villages was full of such unforgettable sights. Lunch was similarly memorable. Our hostess was a 75-year-old tribeswoman, little more than 5ft tall, a mother of 10 and a brewer of rice wine. Hers was a specially doctored variety of the local spirit, the noxious-looking bottle steeped with ginseng and assorted other anonymous roots and leaves, all of them believed by the tribes people to give their elderly extra pep.

Well pep she certainly had, in abundance. We had to down a heady shot as a sign that we were grateful to enjoy her hospitality. As I reeled, my boyfriend jokingly held up five fingers, implying he was game to drink five measures. She quickly held up all 10 fingers. “Ten!” she exclaimed in the local dialect excitedly.

“Ten! Ten!” Quang told us that the old women can often drink their visitors under the table, hardened as they are by their traditional role as party starters at village gatherings. Several shots later, Quang had to lie down, and his excellent commentary went quiet for a while.

Back at the house that night we were given a local footbath, stewing our feet in a herbal brew that looked remarkably similar to what we had been drinking that lunchtime. Then there was a delicious supper of rice-paper spring rolls, sweet and sour pork, carp with tomato and garlic, deep-fried tofu and perfectly nutty white rice.

Lying down on our floor mattresses, in a corner cordoned off from the rest of the open-plan floor space by sheets hung on two lines, we were buzzing with delight at all that we had seen. Our stay in the mountains had been worth those 3.30am wake-up calls, we told each other. It was 10pm. Five and a half hours later… well, our thoughts were a little different. But as we drove back to Hanoi the next day, we knew we would never forget our Vietnamese mountain interlude.